A Brief History of Scrapple

by Cezanne Colvin

I was 21, I had recently spilled both coffee and orange juice on my shirt, and the man sitting in front of me thought I was an idiot.

It was 11 a.m. on a Sunday, and the brunch and leisure crowd was out in full force. I, sadly, was not brunching. I was working as a waitress, and the man had just asked me if the restaurant carried scrapple. Did he mean Snapple? Having grown up on the West Coast, I had never heard of scrapple. I asked him what he meant, and he exchanged a look with his dining companion before returning his gaze to me.

“You know. Scrapple. Hello?” he had said.

No, I did not know.

In fact, I still don’t.

Scrapple is, apparently, integral to the Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine, identity, and lexicon. It has since been described to me as “meat mush,” “good—if you don’t know what’s in it,” and “better than bacon.” Upon further research, the word “congealed” came up in several queries. It also goes by the Pennsylvania Dutch name Pannhaas, or “pan rabbit.” A rural pâté, scrapple has been found on the haute plate at New York City restaurateur’s Ivan Orkin’s ramen eatery in the form of a waffle, which food critic Robert Sietsema called “one of the best dishes of the year” in 2014. It also commonly graces the menu of Pennsylvania’s greasy spoons, having earned the status of a controversial delicacy. Ten out of 10 heart surgeons do not recommend it, and I was even hard-pressed to find a native Pennsylvanian who did. (When I inquired about the offal delight, I was mostly met with looks of concern and the occasional sigh.)

To make scrapple, one boils the less photogenic parts of a pig (e.g., the heart and liver) with the attached bones to make a broth. The entire head of the hog is often included. Then the meat is removed from the bones, cornmeal and flour and seasonings are added, the meat is returned to the pot, and a loaf is created from the miscellaneous pork slurry. Then the loaf is sliced, fried, and served alongside eggs and toast. Some people eat it as is, others smear it with their preferred condiments: ketchup, maple syrup, and apple butter are popular choices. A 2-ounce serving has, allegedly, 120 calories, 4.5 grams of protein, and 23 percent of the Vitamin A that I need for the day. Each gray sliver also packs 2.6 mighty grams of cholesterol-raising saturated fat.

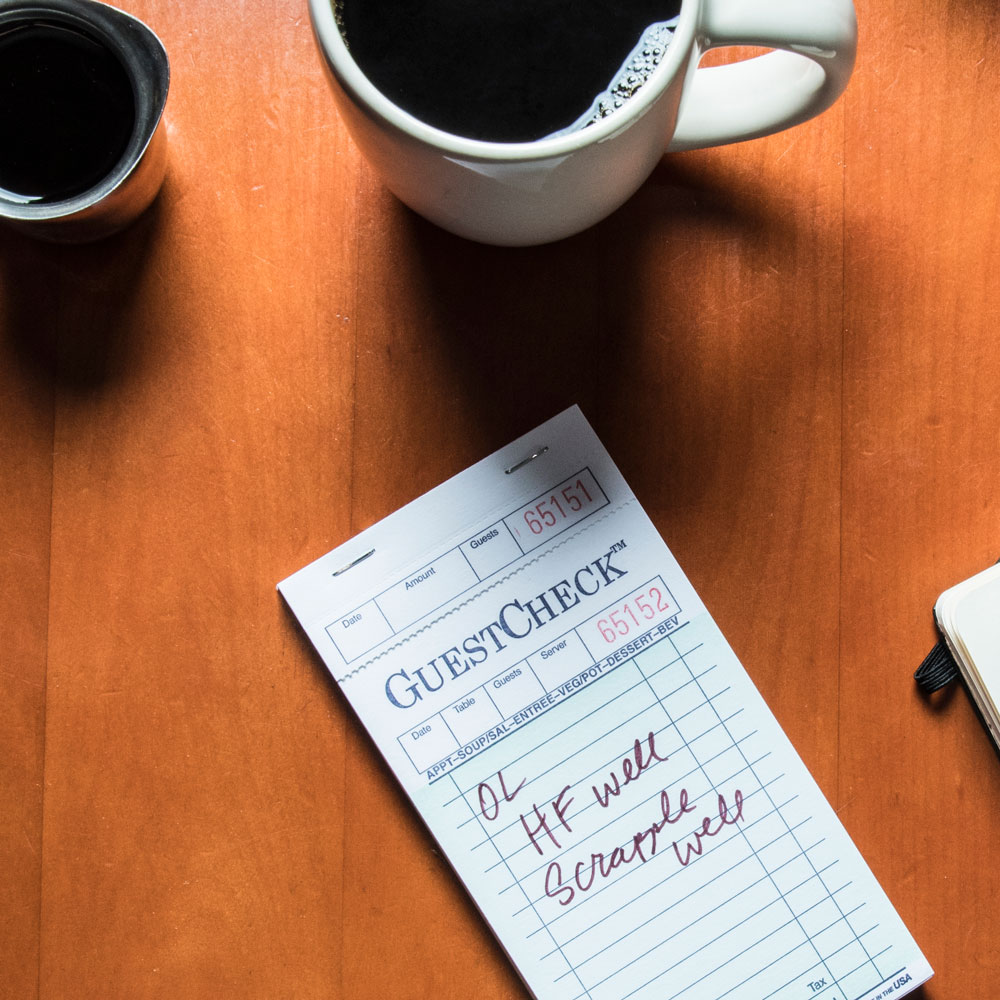

Having invested this much time into learning about scrapple, the only thing left to do was try it. I decided to head to Diner 248 in Nazareth to conclude my research because whenever I drive by, the parking lot is always packed, so if anyone can make pig intestines appetizing, it’s probably them. The diner, owned by brothers John and Stavros Gougoustamos, has been serving up piping hot plates of scrapple—as well as more continental choices like pancakes and Eggs Benedict—since 2009. Diner 248 sources their scrapple from Easton’s R&R Provision, a local meat market. The scrapple comes raw in six-pound loaves, which are then portioned in the kitchen and cooked. The brothers tell me that while some people ask for it in non-traditional ways—deep-fried, mixed into an omelet, or on a sandwich—the most popular request is for it to be “well-done.”

Wanting to be scientific about my tasting, I requested to try it four ways: plain, well-done, with ketchup, and with syrup.

The scrapple came out of the kitchen, and when I saw it, I started to get a little bit nervous. It looked like a thick piece of overcooked gluten-free flaxseed bread.

“Regular” Scrapple

This was reminiscent of when I was on a mission to create the perfect veggie burger. No matter what I did, what recipe I tried, or what the YouTube pseudo-celebrity chef of the moment had promised me, they were always mushy inside. Always. This mirrored that mushiness. One bite was more than enough. I eyed up the remaining three candidates and wondered if maybe this entire thing was a bad idea.

Well-Done

Still reeling from the “regular” experience, I approached my first bite with a little bit of trepidation that turned out to be unwarranted. It was much better than my introductory nibble, and it was surprisingly good. The exterior was deliciously crispy and the interior was cooked enough that I didn’t focus on its texture. Instead, I could focus on the flavor, which was similar

to sausage.

With Ketchup

During my formative years, I was a ketchup-on-everything kind of girl. When I discovered my penchant for all things spicy, however, I soon replaced sugary tomato sauce with habanero dips and chili paste. My return to ketchup-covered grub was a good one: I definitely preferred having a condiment present to cut the meaty flavor a little bit. Immediately, I started thinking maybe A1 sauce would be a great accompaniment. (I was also told that people don’t typically pair A1 with scrapple.)

With Syrup

This was actually delicious. I suspended reality for a moment, the way you might when watching “Avatar” or “Keeping Up with the Kardashians,” and forgot everything I knew about simmering pig snouts and heart-flavored broth. Instead, it was just a fusion of savory and sweet, comparable to chocolate-covered bacon or a McGriddle. I took a second bite and was pleasantly surprised. “Nothing cures a hangover like syrup-covered scrapple,” Stavros said to me. With everything in my being, I believed him.

So, scrapple. Is there a deeper meaning here? That something incredible can be made of discarded parts? That a treasure can truly be made from trash? Probably not. But scrapple is now something I can cross off my bucket list—and I didn’t hate it. Does this mean that I can officially call myself a Pennsylvanian?

As seen in the Summer/Fall 2017 Issue

Click to Visit Our Advertisers